Latinos in California knew how to take advantage of the anti-immigrant law that Governor Pete Wilson supported

When life gives you lemons, make lemonade, say the saying. And that was what the Latino community of California did in 1994 with the lemons that Proposition 187 gave it.

1994 staged a clash of forces in California very similar to the one in the country today. Including the background image: a wall.

The main actress of this scene was Proposition 187, the anti-immigrant electoral initiative put to the vote in November 1994, which sowed and marked the division in the population.

In my opinion, it all started with the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 and its destruction in 1992. That fall came to dry the multimillion dollar games assigned by the federal Congress to the arms industry complex, mainly based in California.

Given this drought of federal funds, the closure of many large companies and many others that functioned as suppliers, or satellites of the former, was swift. Thousands of people lost their jobs in California. The state soon sank into an economic depression.

And the jaripeo began.

That was an election year in California. Republican Pete Wilson faced Democrat Kathleen Brown for the position of governor.

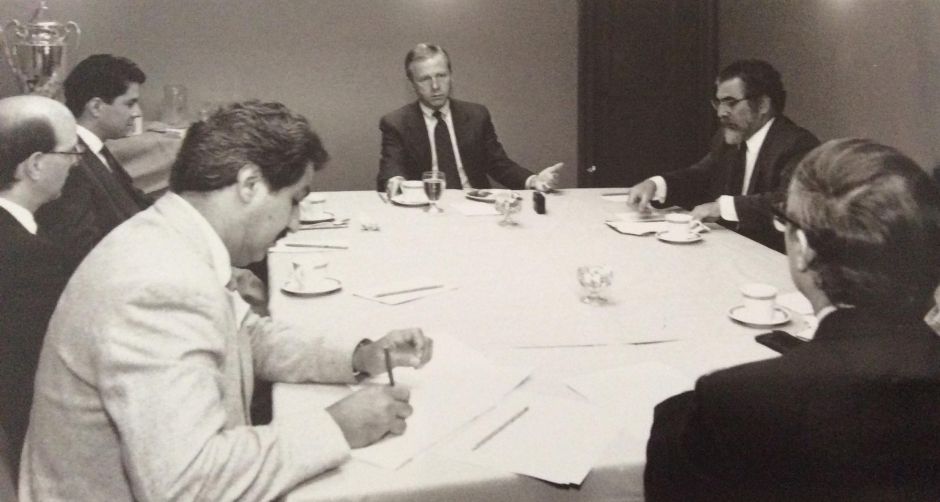

I remember Pete Wilson who, during a conversation with the editorial board of La Opinión, told us that the first act of discrimination against a human being is committed in the bosom of a mother who is denied or inaccessible prenatal care.

Up to that point, Wilson was a Republican with a heart, moderate. But the polls that favored Mrs. Brown appeared. The voices of Proposition 187 intensified, blaming immigrants for all the economic evils the state was going through. The tone of rhetoric against immigrants rose. You just have to remember the image of two human figures with children running in the dark and the voice of a TV ad that said: "keep coming."

Republican Wilson joined that wave of protest. He abandoned the moderate posture of his speech and began to carry the singing voice against immigrants. He won the election. But eventually he lost the war in court and began his disappearance from the political map. And with him, the Republican Party in California went down.

Good triumphed over evil. Proposition187 was declared unconstitutional. But the heat of anti-immigrant electoral rhetoric, its racist and discriminating tone, squeezed the Latino community to its roots. And from its core, renewal movements sprang up: political activism, increased in the number of residents who became citizens, greater electoral participation, moving to other states and the creation of thousands of small businesses.

And the drivers of that revolutionary movement in the Latino community were young people. Enraged by the anti-immigrant rhetoric they heard and could not reconcile with reality in the lives of their parents and families, they took to the streets to protest. The fences in high schools were jumped to march and protest in the streets. Eventually, thousands of Latinos joined them and made huge demonstrations, the largest that are remembered.

In this warm environment and the lack of jobs, many Latinos faced this dilemma: leaving the state or looking for a way to make a living. Many of those who decided to stay, established countless small businesses. And many succeeded in that adventure to such an extent that, Jack Kyser, the guru of the Southern California economy for many years, once remarked that small businesses, mostly created by Latinos, had been the engines that brought out to California from the worst economic depression in many years.

In La Opinion, we created the Business section to offer useful and practical information, as well as to count the startups and successes of these entrepreneurs.

Those who decided to leave, started what came to be called the Latin diaspora. California at that time turned from an immigrant recipient to an immigrant and Latino exporter to different parts of the country. In 1990, according to Census figures, Latinos were the largest minority group in 13 states, a figure that increased to 23 states by the year 2,000.

In La Opinión we intensified our civic journalism projects that led us to talk with readers, gather their concerns and aspirations to transform them into special supplements and more relevant daily news coverage. Many of the young Latinos who took to the streets to protest against 187, are now politicians, activists and professionals in different specialties.

Naturalization figures increased markedly from 1994. According to INS statistics, now ICE, in 1994, 16,403 Latinos were nationalized in California. This figure rose to 44,121 in 1995 and 188,627 in 1996. Between 1990 and 1999, a total of 573,299 nationalizations of Latinos in California and 1,800,168 were registered throughout the country, according to figures collected by Dr. Ricardo Ramírez in a study conducted in 2005

The numbers of Latino voters who participated in presidential elections also increased. In 1988, according to Census CPS figures, 3,710,000 Latino voters went to the polls in a presidential election; 4,238,000 in 1992; 4,928,000 in 1996 and 5,713,000 in 2000. His electoral fervor, as new voters, was greater than that of many natives.

According to NALEO data, in 1994 there were 5,459 elected Latino officials in the country and 20 Latinos in Congress. Today, those same numbers increased to 6,700 and 42 Latinos in Congress. And until 2016, the number of Latinos eligible to vote was already 27.8 million.

Unquestionably, California Latinos knew how to juice a bitter fruit. In the face of the latest attacks, the Latino community in the country would do well to imitate what the Latinos in California did in 1994.

* J. Gerardo López, was editorial director of La Opinión from 1995 to 2004.