The peasants are dying between poverty and injustice; The turn to respond to fraud committed in the United States is up to President AMLO

Óscar Serna, one of 36,000 Mexican braceros, is still waiting for some of the wages they owe him for working in the fields of California and Texas 70 years ago.

Serna is sick and forgets some things, but does not suffer from Alzheimer's. For the past ten years he has had problems with the prostate, to the extent that he has to use a plastic bag as a potty.

He is undocumented, but fortunately, he has emergency Medi-Cal.

"Here I am, walking with a cane, but I can't work anymore," he says.

He was 16 when he was hired to be employed in the agricultural fields of the southern and western United States, mainly in the pinch of orange and grapefruit.

“The first time I came to the United States, I crossed the Rio Grande to the wild, said the old Mexican from Huanusco, Zacatecas. "At that time I was hired to work in the field."

Despite her ills, Serna is one of thousands of former braceros who are still in the struggle with the Mexican government waiting for justice and their money.

However, at 90, he knows he doesn't have much time to keep fighting.

Although he says that he has already begun to forget things, Serna remembers very well that 10% of his paycheck was deducted in an agreement between the US and Mexican governments, without the knowledge of the workers.

Some activists say that the deductions from their salaries, interest and other deductions that were made, possibly the debt would now oscillate between US $ 500 and 1 billion.

How the money was deducted

The Bracero program guaranteed workers a minimum wage, insurance and free housing; however, farm owners frequently did not meet these requirements. Housing and routine meals proved to be well below the promised standards, and wages were not only low, but often paid late or never. The money had been deducted from their salaries and supposedly put into savings accounts. The promise was that they will receive their money once they return to Mexico.

In 2001, the braceros filed a class action suit in a federal court in San Francisco against the governments of the United States and Mexico, along with the Wells Fargo banks, where the money deducted from their checks was deposited and then transferred to the National Bank of Rural Credit of Mexico.

An out-of-court settlement in 2008 was $ 14.6 million, a small fraction of the money taken from farmers.

"It was a very difficult lawsuit to litigate," recalled Jonathan Rothstein, a Chicago lawyer who represented the braceros. “It is a tragedy that has not yet been paid to all workers, but sometimes the fight for justice is a long battle. Sometimes you take steps forward and sometimes you go back. ”

After winning the legal battle, the Social Support Trust was paid to 212,000 exbraceros who lived in Mexico and the United States. However, 36,000 were pending. They live in California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Washington, Oregon and Chicago. So far, the last administration of the Mexican government from 2012 to 2018 did not take action on the matter and are currently awaiting the current president.

Wells Fargo sent the money

Edna Silva, spokesperson for Wells Fargo responded that the total money of the Bracero Program that was sent to Mexico – based on reports from the same Mexican government, in particular the 1946 Ministry of Labor – was $ 34.7 million that were sent to the braceros They returned to their country.

In 1946 the Mexican government suggested that $ 6 million had already been reimbursed.

Did Wells Fargo know that Mexican braceros were never informed that the bank was deducting 10% of their salaries?

"As the diplomatic agreements between the US and Mexico governments specify, it was the responsibility of the Bank of Mexico to distribute the funds to local Mexican banks for the benefit of the braceros when they returned to Mexico," he replied. “Wells Fargo had no role in reconciling the savings fund process or individual relationship with the braceros in Mexico. (However) We recognize the concerns of the braceros in this difficult situation. ”

The money from the agreement was included in the Social Support Trust established by the government of former Mexican President Vicente Fox. He continued with his successor, Felipe Calderón, but was ignored by President Enrique Peña Nieto, who served from 2012 to 2018.

In late October, Oscar Rafael Novella Macías, Mexican secretary of the Committee on Migration Affairs of the House of Representatives, acknowledged in an open session of parliament that the Mexican government can no longer waste time on the issue of the bracero because “ They are sick, old and in poor health. We have to make political-legislative efforts. ”

The Mexican representative Julieta Kristal Vences Valencia, president of that commission, requested 500 million pesos ($ 26.3 million dollars) in the 2019-2020 budget to make payments. You beat Palencia until the end of this edition had not responded to numerous requests for an interview with La Opinión.

Time is running out

Baldomero Capiz, an activist who was coordinator of the Binational Union of Ex-braceros, said they are still waiting.

"We have been struggling for the past 20 years to recover the savings fund for farmers," Capiz said.

So far, the only way to get the money back to the braceros is for the current administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to recognize the histórica historical deduction ’, although that decision is still in debate.

"What they have done with older adults is a violation of their human and constitutional rights as Mexicans residing in the United States," said Rosa Martha Zárate, leader of the ExBraceros del Norte Alliance. "When we requested that social support of 38,000 pesos ($ 2,000), we had to take the old people to Mexicali to notarize their letters, obtain more documents, apostilles and a whole tangle of procedures."

Sitting in a plastic chair in the front yard of his son José's house, in San Bernardino, and leaning on a mesquite cane, the Bracero Serna reacts to the situation.

"Our money was stolen, what are we going to do?" Said the nonagenary.

Meanwhile, in his humble home in Lincoln Heights, another bracero named Leobardo Villa, a native of Zacapala, Puebla, says that, at 87, he is already tired of so many protests and not being paid.

“I came to work in the fields of California and Yuma, Arizona, at the age of 18 to plant watermelon, melon, all kinds of vegetables,” he says. “Like all my classmates, we left the skin in the furrows and railroad tracks; but we are not asking the government for a gift, but what will return to us what corresponds to us ”.

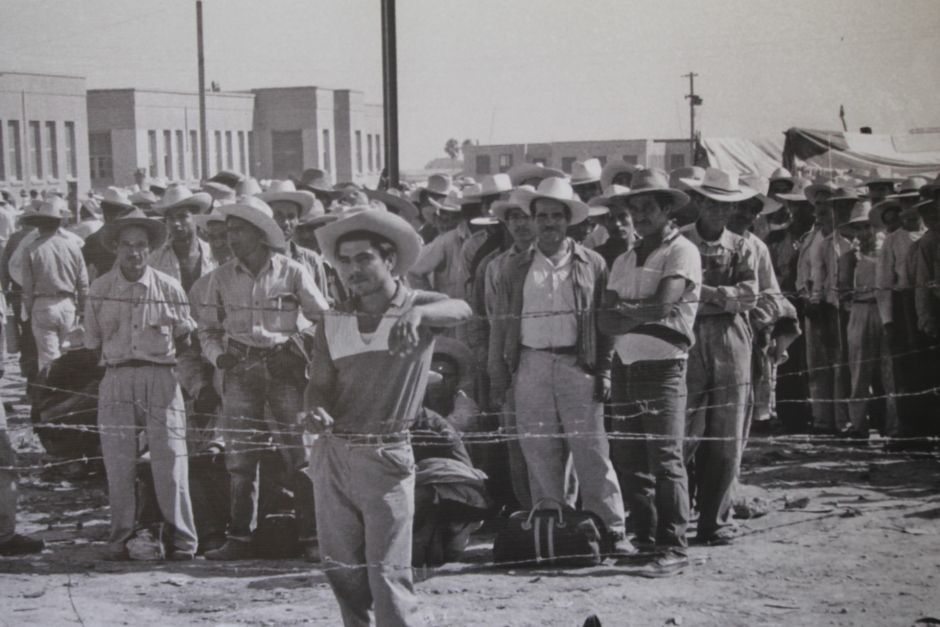

The bilateral employment program between Mexico and the United States lasted from 1942 to 1964.